Inheritance. |

Philosophy

and Nonsense

(Thoughts about writing,

education, and experience.)

Presented by Forrest D. Poston

The first goal of teaching is to strengthen, deepen and refine our intrinsic love of learning. All other goals and all methods must stem from that idea. Any that do not support that goal must at least be questioned and adjusted, if not eliminated. Otherwise, we are not teaching but training. Think, I dare you.

|

Stories, and that

has made all the difference. |

Beyond the

Genes, We Inherit Our Dreams: The Story of a

Father by

Forrest D. Poston Born eight years apart, my oldest brother and

I knew Dad differently, the same father but a

different man in a different time. Greg knew the

younger days, and though the first seven years were in

the coal camps, they were largely days of bright

expectations mixed with mercurial moments. And

Greg was a more traditional teenager with a more

traditional life that included a lot of time away from

the house after a certain age.

Born eight years apart, my oldest brother and

I knew Dad differently, the same father but a

different man in a different time. Greg knew the

younger days, and though the first seven years were in

the coal camps, they were largely days of bright

expectations mixed with mercurial moments. And

Greg was a more traditional teenager with a more

traditional life that included a lot of time away from

the house after a certain age.Despite differences in age and the routes our childhoods took, we both inherited a great deal, not all of which seems to be genetics. Oh, we have the nose, though Greg’s is smaller than Dad’s was and mine is smaller than Greg’s, and I think Dad's was smaller than uncle Carl's, Dad's older brother. That nose still distinctly a family trait, but we also inherited a need to tell stories. Unlike the nose, that need didn't shrink as it crossed generations, even if we talk much but reveal little. Science now tells us that we pass along more than just the basic genetic coding, and it's as if storytelling was in us when we were born and grew with each breath. But those eight years separated me in ways I only slowly understand, still grasping for it as I move a bit closer to Dad's last age. Time and separation keep showing me a different father, deeper in some ways, perhaps, often sadder, and hiding so much else. That's not quite fair. It's not so much that he kept things hidden as that he rarely offered, and I rarely asked. It’s as if i was always a little late in learning what to say, too slow in saying. I was late in learning that he could play music by ear, and by the time I heard him play his harmonica, coal mines, crawl spaces, and Camels had taken his breath. He told me some stories, revealed a piece here and there. I knew that he dropped out of school after 8th grade. He told me that it was because he was bored, which was probably true, but he didn’t mention that he already had more siblings and half-siblings than one person could feed, and Dad had been old enough to remember the even tougher times when his father had walked out. So Dad went to work in the mines, which probably also began his determination that his own kids wouldn’t grow up in the coal fields. That promise he made to himself, made for his family, was one of the few things that he ever told me flat out, not buried in a story, a promise too important to conceal with plots and jokes. He drove a coal truck, a taxi, a newspaper route, worked in the mines, painted company houses, worked for Carl, working more jobs than I ever knew about, losing more of them than he would tell, and for reasons I would eventually come to suspect  and

understand. It wasn’t so much that he couldn’t

live by other people’s rules. He just couldn’t

live on other people’s time. Maybe it's a

control thing. Yeah, it runs in the family. and

understand. It wasn’t so much that he couldn’t

live by other people’s rules. He just couldn’t

live on other people’s time. Maybe it's a

control thing. Yeah, it runs in the family.Dad kept that promise. The family moved out of the coal fields. And they moved back. They moved again, moved back, tried working and living with Carl and his family in New York, moved back. Just a week before I was born, the move took hold. Coal dust is likely in my blood, but it was never in my lungs. Because of that move, I grew up with a different vision and different expectations. We were in a small but growing town where a large, new company helped build new schools and brought in new people, not just laborers and merchants but executives, something you didn't find living in coal camps. We may have lived in the working class part of town, but there was management in the air. That's what filled my lungs and left me a bit separate from brothers, parents, and myself. Memories of Dad from that time seem to revolve mostly around what car or truck we had more than Dad himself. When the storm of '63 hit, Dad came home long enough to unplug the tv before going back to the restaurant on the corner, back to the stories, I suppose. Greg finished high school and went on to study electronics, and his hands, like Dad’s hands, seemed able to do anything, had the same need to be used, to feel the wrench, the wood, the sweat, and the craft. For them, physical work became an art. I went to college and only later learned to wield a shovel well and hammer a nail more often than my finger. Dad was proud when despite assorted detours I became the first in known family history to graduate from college, but we were divided more than ever. We could still talk about the Cleveland Browns and the Cincinnati Reds, and I had even learned to do it without arguing, but that was pretty much the limit of our talks, which is probably why I love the father-son moments in movies such as "Breaking Away", the ones where the father and son have that great revelation that changes their relationship, that moves them past not just the generation gap, but the transition gap.  And I

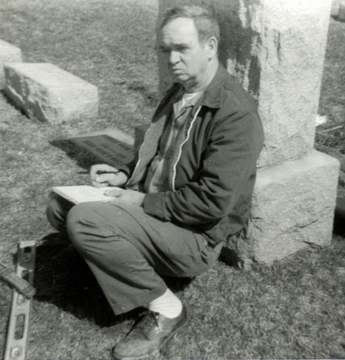

eventually worked with him in his plumbing and setting

monuments, learned to dig ditches with straight sides

and flat bottoms even if they were going to be filled

in as soon as the pipe was laid. He could clean

the ground with a shovel better than most people use a

broom on a floor, which I never did learn, but I did

learn to leave a place better than I found it whether

that meant appearance or the way a job was done.

By the time I was 21, he told me I did a good job at

something, and eventually he even said that I was like

an old engine; I worked pretty well once I got

started. The praise meant a lot. I didn't

speak. Somewhere along the line, I began to realize

that he probably thought that I looked down on him or

wasn't proud of him. Even in my youngest dayst,

that wasn't true, and much of what he could do was a

wonder to me. He never asked, and I never

said. He was the main reason for what I had

become, had made it possible by keeping that promise

decades earlier, but what I had become seemed

different, almost foreign to him, I think. In

ways, I was foreign to myself. And I

eventually worked with him in his plumbing and setting

monuments, learned to dig ditches with straight sides

and flat bottoms even if they were going to be filled

in as soon as the pipe was laid. He could clean

the ground with a shovel better than most people use a

broom on a floor, which I never did learn, but I did

learn to leave a place better than I found it whether

that meant appearance or the way a job was done.

By the time I was 21, he told me I did a good job at

something, and eventually he even said that I was like

an old engine; I worked pretty well once I got

started. The praise meant a lot. I didn't

speak. Somewhere along the line, I began to realize

that he probably thought that I looked down on him or

wasn't proud of him. Even in my youngest dayst,

that wasn't true, and much of what he could do was a

wonder to me. He never asked, and I never

said. He was the main reason for what I had

become, had made it possible by keeping that promise

decades earlier, but what I had become seemed

different, almost foreign to him, I think. In

ways, I was foreign to myself.He wasn’t a tv Dad. He didn’t teach me how to fish, and the one time he gave in to my begging to toss a football for a while, his bursitis caused him to suffer for days, even if I didn’t find out for years. He was one of the most frustrating men to ever walk the earth. He delighted in arguing for its own sake, and his words were often prejudiced, though his actions never were. Still, I never looked down on him, and I would never accept any offer for a chance to go back and change fathers, no matter who might be offered, not even in exchange for one of those movie revelations. Of course, that could also be because of the stubborn streak that runs deep and wide in the family. Just as many important things were left too late for me to say, some of the most important things I learned about him came late and from other sources. Not long before his health forced him to retire, I was helping with some labor at the local publishing company when the owner came by to chat. That was when I heard the story of the company growing too fast and taking on more work than its equipment could handle. That’s when I heard how Dad took that 8th grade education, designed, built, and installed a new ink-supply system from standard plumbing parts.....and that  after two

years that system still had the process fast enough to

handle even more work and had yet to require any

repairs. Not every engineer has a degree. after two

years that system still had the process fast enough to

handle even more work and had yet to require any

repairs. Not every engineer has a degree.More stories with the bigger revelations came even later, very late, stories told as I stood beside Dad's casket at the viewing and talked with his friends that I hadn’t seen since childhood. It was Abe, the barber who cut my hair for my first 7 years who told me that Dad would spend 20 minutes fixing a faucet and 4 hours sitting at the kitchen table drinking coffee and telling stories. That’s when some things fell into place. Dad couldn’t live on other people’s time. That’s why he eventually, absolutely had to work for himself. We never went without what we needed, but we were never going to have a pile of money in the bank. I don’t know if he needed the time to tell the stories or if the stories were just a way to control his time, but it had to be that way because he was that way. He wouldn’t rebel or try to change the world, but he needed that bit of control. There were things that he had to do because it's what fathers do for their family, and there were things that he had to do because they were in his bone and blood. And then Dr. Monroe,the family doctor through my early years told me the biggest story of all, another side of a story I thought I knew, another side of the man I thought I'd known. The man who had done so many things beyond education and experience, who had done more than anyone would have imagined had done one thing beyond the rest, and I'll never know the cost. When I was seven, my mother died of a brain tumor that had been mis-diagnosed as early menopause at the nearest hospital. Dad suspected the mis-diagnosis, but this was mid 1960s rural West Virginia. Hospital choices were few, roads narrow and slow, and time and money were both limited. So every morning, Dr. Monroe arrived at his office to find Dad waiting on the stoop, going in each day to read the medical books until he had to go to work, back when he still worked for someone else. And it was Dad, with his 8th grade education, who made the correct diagnosis and who knew as well the prognosis. His hands could do anything from drawing to making any hand tool an artist’s tool, and his brain could do things formal education couldn’t give, but this was something neither hands nor head could fix. This was beyond his control, and I don't think he made anymore promises to himself after that.  In all

the years after, he only told me one story about my

mother, the story about the first time they met when

he gave her and another girl a lift. He told me

that it was then that he told himself that was the

girl he was going to marry. When I asked him if

the story was true, he only said, “I did, didn’t

I?” I think now that the story was true, and

that making that diagnosis killed the father that Greg

grew up with, changing him into the father I grew up

with, a father with an impish side who could still

enjoy a water fight but who was often up late watching

bad movies. Sometimes tv becomes an electronic

campfire, able to keep the darkness just far enough

away. In all

the years after, he only told me one story about my

mother, the story about the first time they met when

he gave her and another girl a lift. He told me

that it was then that he told himself that was the

girl he was going to marry. When I asked him if

the story was true, he only said, “I did, didn’t

I?” I think now that the story was true, and

that making that diagnosis killed the father that Greg

grew up with, changing him into the father I grew up

with, a father with an impish side who could still

enjoy a water fight but who was often up late watching

bad movies. Sometimes tv becomes an electronic

campfire, able to keep the darkness just far enough

away.The last time I saw him, he was in the hospital, as he had been many times in the recent years, but he was doing better. I had just gotten my Masters diploma and had been teaching as a graduate assistant for a few years, so I got to show him the diploma for his birthday, knowing that he  was

proud and happy to know that I had a career in mind,

happy that he no longer had to worry about his

somewhat different son. was

proud and happy to know that I had a career in mind,

happy that he no longer had to worry about his

somewhat different son.The truth, however, is that I’m not so different, or at least I hope that I’m not. I think that in more ways I am what he might have been if he had been born with a shot at the same education, even if part of me believes he would have done much more with it. Whatever might have been, his blood and spirit are in me and the stories that I tell, living on my own time. I’m glad that I got to show him that diploma, glad to know that he was proud, but as I showed it to him, I also knew that I should tell him how proud I had always been of him, how I could never be anything but proud that he was my father. I knew that I should say that and so much more, but neither storyteller said a word. He was doing better, and we’d have time. We would surely have time, plenty of time. I was a little late in learning, and a little slow in saying. A few days later, he died. A Call For a Father

(by Forrest D. Poston)

Dawn coming soon, darkness yet holding sway, when the phone rings. “The doctor says you should come.” Bags always packed, we leave with practiced hurry. Determined, stubborn, he wins again, defies not merely death but doctors, stymies tests, refutes statistics. We have more time. We have two years of defiance we love, pre-dawn calls we hate, knowledge we fear. But another dawn has come, a day sunny and safe, a day for errands run slowly, knowing The Call won't come; breathe. Ginny met me at the door. The call had come about 2PM. There was no more need to hurry. E-mail Back to the Home Page |

Writing and Education Autobiography Challenge Considering Conclusions Considering Introductions Four Meanings of Life Godot and the Great Pumpkin A Major is More Minor Than You Think The Poetry Process (A look at 4 versions of a poem.) Thoughts About Picking a Major Quick Points About Education Quick Points About Writing Reading Poetry and Cloud Watching Revising Revision Reviving Experience Reviving Symbolism Using an Audience Videos What Makes a Story True? What's the Subject of This Class? (Being revised.) Why Write? Writing and Einstein (The Difference Between Information and Meaning) Writing and the Goldilocks Dilemma Links to Other Sites |

Other Essays and Poetry Something Somewhat Vaguely Like a Resume Alec Kirby, Memories of an Earnest Imp Being Like Children Beyond the Genes (Dad) The Blessing and the Blues Bookin' Down Brown Street The Cat With a Bucket List David and the Revelation The Dawn, the Dark, and the Horse I Didn't Ride In On (an odd, meandering, semi-romantic story) Getting a Clue Ghost Dancer in the Twilight Zone The Hair Connection and the Nature of Choices I Believe in Capra The Mug, the Magic, and the Mistake Roto, Rooter and the Drainy Day Sadie on the Bridge Trumpet Player, USDA Approved Videos Poetry Selected Poems The Poetry Process Links to Other Sites |